By Bill Jennings

from issue 27-6

In our last commentary on sonar, we discussed depth sounder principles and noted that while they make you aware of what is beneath your boat, they do not let you know what you are about to drive over. Evolving technologies of SONAR, (Sound Navigation and Ranging) are changing this. So how might this translate to new electronics for you and me?

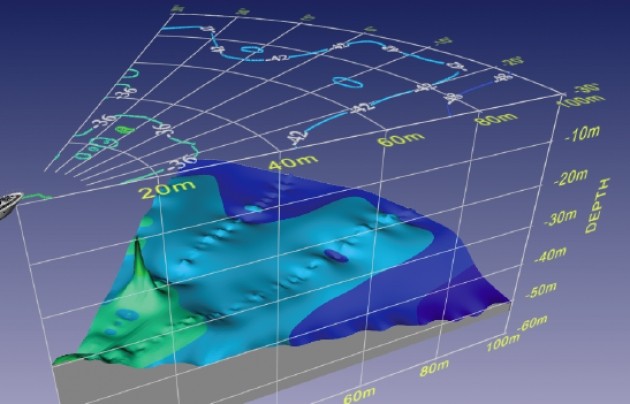

American scientists after WWII, began researched sonar systems for the Navy. During the 1950’s, Westinghouse (now Northrop Grumman), produced some side-scan sonar systems for the military. A single conical-beam transducer was mounted on the side of research vessels, hence the name side-scan. Next, a transducer was applied to each side of the vessel, in order to cover both sides of the vessel track. The “side-scan” emitted conical or fan-shaped pulses toward the seafloor in a wide angle, perpendicular to the path of the sensor through the water. The intensity of the acoustic reflections from the seafloor of this fan-shaped beam was recorded in a series of cross-track slices, then stitched together, along with forward direction and speed, to form an image of the sea bottom.

The first commercial applications for Sonar units date back to the mid-sixties, when dual-frequency side-scan sonar was used for various public projects. Sound frequencies used in side-scan sonar range from 100 to 500 kHz, the higher frequencies producing better resolution and the lower, greater range. The term ‘Broadband’ refers to simultaneously transmitting several frequencies, or wider band of frequencies, from a single transducer, in order to increase image accuracy. A shorter distance between the transducer and the bottom produced a better image, so in order to achieve optimum resolution in deep water the side-scan transducers were placed in a “towfish” and pulled by a “tow cable”. Typically these side-scan sonars search a swath 60 to 160 feet wide at about 2 miles per hour, although other ranges can be used depending upon the size of the target object. Initially, commercial side-scan images were produced on paper records. Now, data is stored on computer hard drives. Matching GPS location information allows the searchers to return to any point in the image for further investigation or recovery.

Sonar today has many commercial applications; such as imaging large areas of sea floor, detecting hazardous obstructions, monitoring pipelines and cables, fisheries research and locating drowning victims. More recently, developers recognized that a market existed for sounders that could provide recreational boaters with more information than simply the depth of the water beneath their boat. Having boated regularly in the Vancouver area, I’ve always looked for technology that could make boating safer in the log-infested coastal waters of BC. Advancing technologies in the form of affordable forward looking sonar would provide valuable information for all boaters. Affordable ‘FLS’, or ‘Forward Looking Sonar’, apply the same principles as commercial sonar, but point the fan shaped pulses forward, so that pleasure craft can learn about potential problems ahead. This is welcome news for those who ply the BC coast as well as many others who explore unfamiliar waters in other parts of Canada.

Unfortunately, the recreational FLS units on the market to date, have been best suited for buyers with modest expectations. One reason is that FLS is only able to register forward images that are within five times the distance to the bottom before encountering bottom return interference, so if you were in 30 ‘ of water, the unit would only record 150′ ahead. But even when forward objects are within range, the electronic processing of compiling detailed images, from what is under the boat, is much easier to do than shoot clear images of what you are about to drive over.

Navico is currently the world’s largest marine electronics company, and is the parent company to Lowrance, Eagle, Northstar, Simrad and B&G. In Canada, Navico products are distributed and serviced through CMC Electronics, in Montreal. Each of these well known companies is working together to develop recreational FLS systems. Other companies active in Sonar development include, Raytheon, EdgeTech, CMax, Imagenex, Sonatech Inc., WESMAR, Marine Sonic Technology, EDO Corp, EchoPilot, and Deep Vision.

Two currently available examples of affordable units are the “Ultrascan” from Interphase and the “Sonar Engine”, SE-200. The Ultrascan claims a forward range of 1,200′ and a depth of 600′ for a cost of around $5,000. The SE-200 ‘black box’, will plug into existing chart plotters, radars or VGA flat panel displays to add FLS to your existing navigation electronics and cost even less.

But if you want more from your electronics than to impress friends with a helm full of screens, you need to be specific on the application for the electronic device you are purchasing. Is it for fishing or increased knowledge of the sea bottom? Is it for offshore use, or inland waters? Presently, I would define FLS technology as an imperfect technology that is currently in transition. Therefore, be sure to insist that the specialist who sells you a unit also guarantees that it will meet up to your expectations. And if you are like me, it needs to be easy to operate, so that you do not have to go back to school, or read volumes of manuals before turning it on. For most of us, the best plan might still be to have your first mate on the bow with a good pair of binoculars.