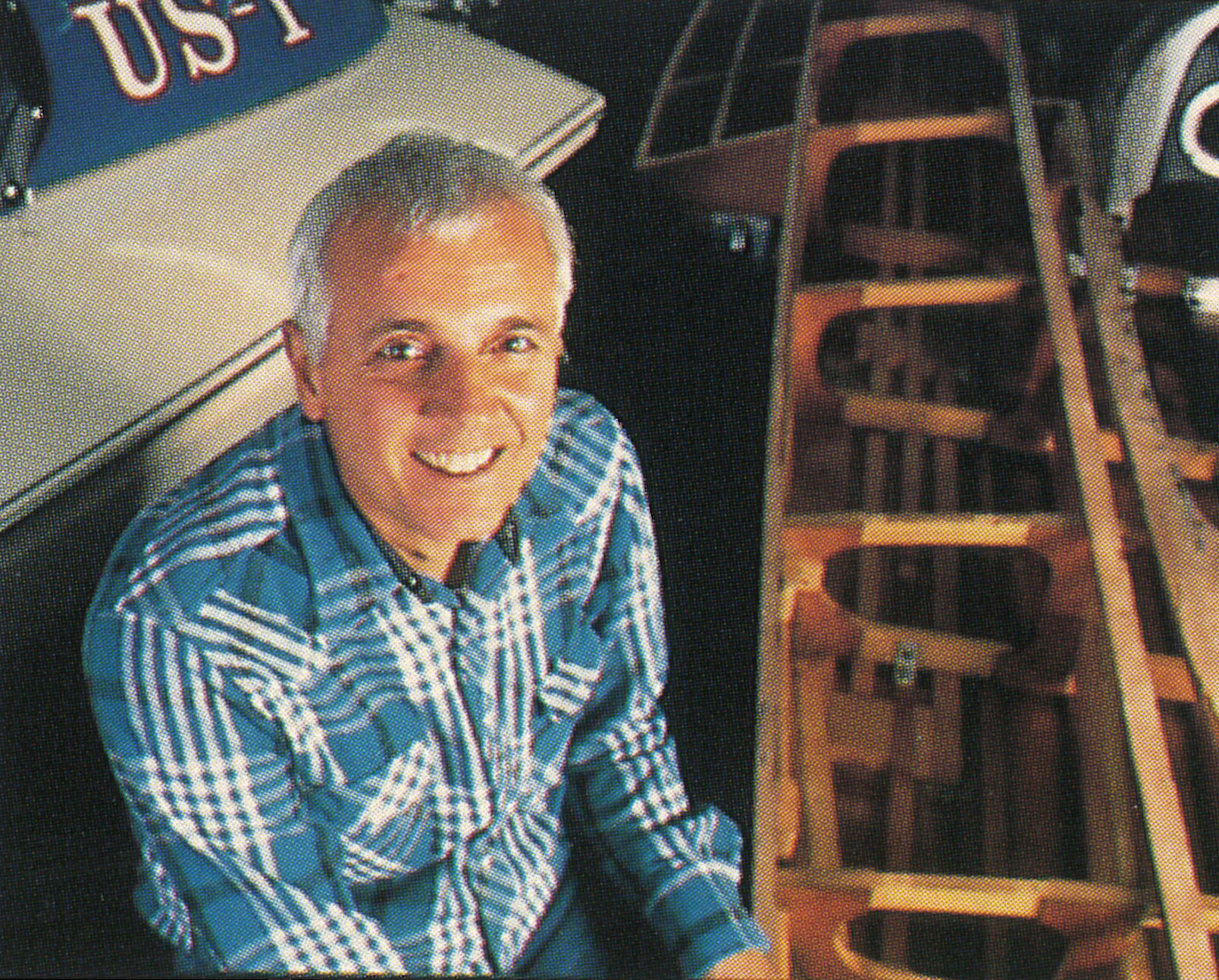

Henry Lauterbach created some of the world’s premier race boats. Now collectors are hot for his hulls.

Stephen M. Schelb

As the minute hand clicks from 11:59 AM to noon, Henry Lauterbach locks the door of his Suffolk (pronounced “Suff-ick”), VA, shop and heads off to a local greasy spoon for lunch. At the age of 77, he has cut back his hours and follows a practised daily routine: in at 7:30 AM, coffee break between 9:30 and 10, the aforementioned lunch until 1. Henry cuts out at 4:30 PM.

“I used to work 16, 17, or 18-hour days and was taking home only about $125 a week,” Lauterbach says over a club sandwich at lunch. “I finally realized I was doing double time for one week’s pay, so I eventually cut my hours in half. Then I only worked 7:30 AM to 8 or 9 at night.”

Lauterbach says it never bothered him working all those hours because he loved what he was doing.

“You’re only going to make one thing in life – a living,” he says. “That’s why I never thought about retiring. You hear people talk about retiring so they can do something they enjoy like play golf or something. I’m already doing something I enjoy.”

Aside from a living, Lauterbach has made something else in life: boats. At one time, he was one of the world’s premier boat builders. His handmade wooden hulls were sought after by racers all over the United States, Canada, and even Europe. For two consecutive years in the early 1950s, Lauterbach hulls swept every class at the American Power Boat Association Inboard National Championships. During his prime, Lauterbach built only three or four boats a year and was working on a two-year backorder.

Although a recent safety rule change rendered existing Lauterbach boats obsolete for competition, his boats are now equally sought after by discriminating collectors.

A 23-year-old Lauterbach began working in the Norfolk Naval Shipyard, VA, in 1941. He worked in the shipyards during World War II on 26-, 34-, 36-, 40-, and 50-foot motor launch whale boats, gigs, personal boats, and worrys.

Is this where he learned the craft of boat building?”

“Hell no,” he says. “I went over there to teach them. I learned how to do this on my own.”

Lauterbach grew up in Hilton Village in Newport News, VA. While a youth, he would show up whenever he saw someone building a boat and offer to help them. This was, then, how he acquired a working knowledge of the art of boat building.

“I worked in three or four yacht yards before going to the Naval Yards because of my experience building sailboats as a kid,” Lauterbach says.

“I picked up most of my woodworking skills on my own in high school. I had this teacher in shop class that was very knowledgeable, and he was good at passing his knowledge along.”

The Shop

After lunch, Lauterbach returns to his shop, a nondescript orange warehouse he built specifically for his business about six years ago. Inside the front door, and to the left, is his office; it’s a 10’ x 20’ enclosed cubicle.

An antique wooden desk sits inside the door to the office, and a kerosene heater provides warmth from the back of the room. Inside Lauterbach’s desk, itself covered by unorganized stacks of catalogues and papers, is a drawer full of loose photos documenting his career as a boat builder. Start talking about boat racing with him, and Lauterbach will likely slide open the drawer to shuffle through his photos. There is no photo album or any other semblance of organization, yet Lauterbach always seems to find the picture he seeks. Some of the black and whites date back more than 50 years.

Outside the office is an expansive warehouse. Along the north wall, about eight feet above the floor, is the “mezzanine” where “most of the work is done.” Strewn about the dusty floor are several table-sized power tools and a couple boats on trailers, each in a different state of renovation. One of the boats, the A-43 Lauterbach Special, is nearly finished; it’s covered by a tarp at the shop’s front. The boat is a replica of the original and was rebuilt – entirely from photographs – for Tom D’Eath after the original could not be located. Lauterbach took almost all of 1994 to build the boat in exact accordance with its original specifications.

Lauterbach, himself, is dressed in a standard issue mechanic’s uniform: blue chinos and a white, long-sleeve Oxford complete with a scripted “Henry” embroidered on a patch over his left breast.

Lauterbach began his career building sailboats. He built his first sailboat at the age of 12 and, by 1948, had progressed to building powerboats which would go on to win races in every subsequent decade. His brother, Norman, studied architecture and marine engineering in college. Norman designed Lauterbach’s first powerboat.

“I put it in the water, and it started doing funny things,” Lauterbach recalls. “We finally got it balanced and shoved it in the corner and built another one – that was in ’48 or ’49 – for Dan Wilson. Then I built another one for his brother, and it was called The FoMoCo Kid.”

Lauterbach built his last sailboat in 1950 and went into racing full time when he realized his boats could win.

His first boat to ever win a race was just the third he’d built. It was 1949, and W. Curtis Martens – driving a 135 named Marbel – captured both the national championship and the high point championship. Three years later, Bob Rowland’s 266 You-All did exceptionally well and lost only one heat in two consecutive seasons of competition. The winner’s list continued to increase every year as Lauterbach hulls became more and more popular.

Between September, 1959 and December, 1960, Lauterbach – riding high on his success – began building and moving into a new shop. By that time, there were six other manufacturers competing for his business. Lauterbach’s orders began to slow.

“I didn’t have any work at the time, so I built a boat for myself and it started running in first place at every race I went to,” he recalls. “About that time, this guy came up and wanted to buy my boat. He asked my price, I told him, and he left. He came back with this big wad of hundred-dollar bills to pay for the boat.”

Standing there with more money than he’d seen in quite some time, Lauterbach faced a decision: go out and celebrate or bank the money and begin anew. He chose the latter.

“From that time on, everybody wanted my boats,” he says. “It wasn’t two months before I was backordered again.”

By now, Lauterbach had some serious competition. He turned to one designer, Rich Hallet, for ideas.

“I looked at his boats to pick up things that I could take back to the shop and put into my boats to make them better,” he says.

Hallet wasn’t his only inspiration. In 1957, an Italian team arrived at the Orange Bowl Regatta. Their success gave Lauterbach an idea for a gearbox with a 1:1 ratio.

“I watched them run, and I couldn’t believe how balanced the boat was,” he says. “That fellow couldn’t speak much English, but I went over to him and asked how they did it. It was a normal 100-cubic-inch engine, and I asked him how much horsepower they were getting.”

He was astounded at the reply: 700 HP at 9,000 RPM. The Italian team had installed a gearbox with a 1:1 ratio for a simple reason. The horsepower produced by its engine wanted to torque the boat right. The gears, however, caused the prop to spin in the opposite direction and effectively torqued the boat left. The boat was thus balanced out.

Boat Design Techniques

Contrast our age of computer-assisted design – in which a boat’s purchase price can climb into the six figures and beyond – with Lauterbach’s process. He shied away from technology, opting instead for the old-fashioned method.

“I just got on the drawing board and worked it up,” he says. “My boats were in a constant state of evolution. Some of the changes were just the types of things you lay in bed and think about. You know, where you think, ‘maybe this will work, maybe not,’ but nothing too radical.”

During the 1950s and ’60s, Lauterbach gradually widened the sponsons and made his boats a littler longer. By the mid-Sixties, he had widened the transom to put a tunnel underneath the boat.

He had also begun dabbling in construction of Unlimited boats during the mid-Fifties, having built a boat for George Simon. In 1974, Lauterbach tried again, unsuccessfully, to form a client base by building an Unlimited for Carl Kearns and Walt Carter.

“I never had much luck with Unlimited customers because, before we could get finished, they would run out of money for it,” Lauterbach says. “The one I built for Kearns and Carter was running 105 [miles per hour] in 1980 with the two Chevys in it when everybody else was running 125. With the two Chevys in it, it would have been competitive when it was built in 1974.”

Lauterbach The Driver

Although he’d been racing as long as he’d been building, Lauterbach called it quits as a driver in 1956 to pursue boat building full time. When Mildred Ritner died in 1959, Ray Ritner asked Lauterbach to fill in for the remainder of the season. Lauterbach did; not only did he nab an APBA record, he won the US-1 high points championship.

“I raced just a couple of times after that,” Lauterbach says. “I was getting a lot of pressure from home because my wife at that time didn’t like me racing. It was just easier to stop driving.

“Even up until the last couple of years, I’d like to get out and run a heat or two, but I’ve never done that.”

Although Lauterbach now spends his time with repair or restoration work in his Suffolk shop [ed. note: Mr. Lauterbach passed away in 2006], he says he has often considered building one more boat before calling it quits.

“If I was to build a new boat, it would be a cabover with an enclosed cockpit for sure,” he says. “It would most likely be a pickle fork design, and it would be modified quite a bit, but I don’t know if I’m ever going to build another boat.”