Unraveling the mystery and misunderstanding of propeller slip.

By Steve Sandler

Selecting the right propeller is the easiest and cheapest way to improve performance. Propeller test results are frequently published and new propellers reviewed in boating periodicals. Propeller slip factor is usually calculated and included in these test results. Unfortunately, slip is often misunderstood and its value overstated as a key factor in selecting the best propeller.

In this article I will apply science to understand how a propeller really works, the meaning of slip, and its importance in propeller design. If you’re interested in the science read on. If not, the following summarizes our conclusions:

A propeller doesn’t propel a boat by screwing itself through the water like a screw in wood.

Slip does not define propeller efficiency, so a propeller with a higher slip factor is not necessarily less efficient than one with a lower slip factor.

Don’t get hung up on slip factor. The best propeller for you is the one that best satisfies your performance objective, e.g. top speed, hole shot, or mid-range acceleration, independent of calculated slip.

Propeller Theory 101

Propeller Theory 101

Most physicists believe that a propeller generates thrust in accordance with the principles of Newtonian Mechanics. Newton’s second law of motion states that force is equal to the rate of change of momentum. Now, the momentum of an object is the product of its mass and velocity. In the case of propellers, the momentum of the water in front of the propeller is increased as it passes across, the rotating by the propeller is equal to the rate of change of this momentum.

This same principle governs the thrust developed by propellers, jets, and rockets. It explains why an airfilled balloon flies out of your hand when its nozzle is released. A propeller doesn’t screw its way through the medium in which it’s immersed. The force of the water exhausted by the propeller creates an equal and opposite force against the propeller. The force against the propeller is the thrust that propels the boat.

Okay, so how does the propeller increase the momentum of the water across its blades? If you look at a propeller, you’ll notice that its cross section, or chord, is shaped like an airplane wing. As air passes around it, a wing creates low pressure above and a high pressure below to generate lift. The amount of lift generated is a function of airfoil shape, speed of the air flowing across its surfaces, and angle at which the air flows. This angle is called angle of attack. Since a wing typically has a complex shape, it is difficult to determine a reference for angle of attack based on wing geometry. This problem is resolved by assuming that zero angle of attack is the angle that results in zero lift, and taking geometric angle measurements from that reference. Lift increases as angle of attack increases. If angle of attack becomes too large, airflow is disrupted and lift drops off. This is the condition known as wing stall.

A propeller generates thrust similar to the way that a wing creates lift. The low pressure at the propeller blade back draws in water while the high-pressure side on the blade face forces it aft with greater velocity, thereby increasing its momentum.

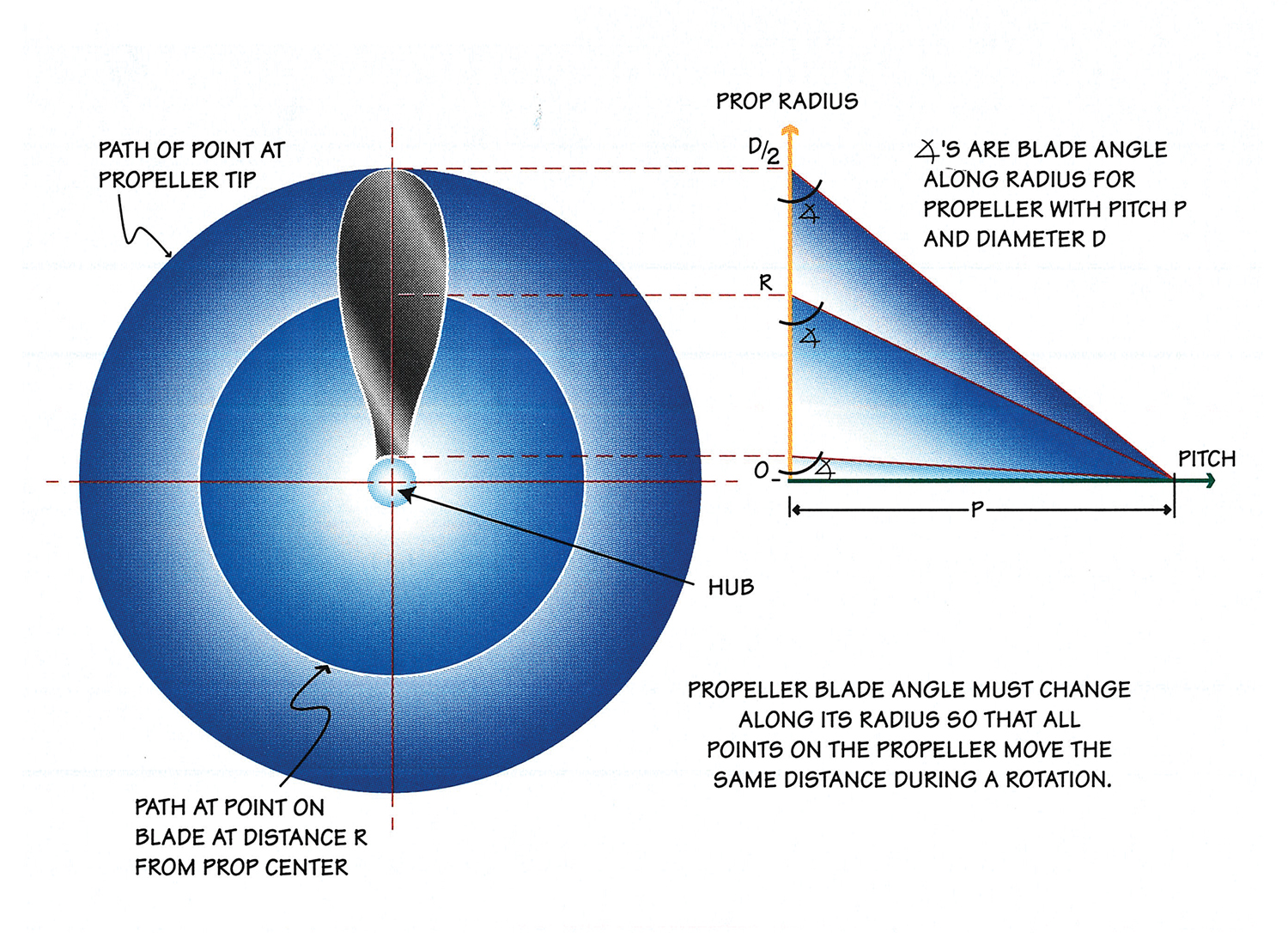

However, there is one important difference between a wing and a propeller. While a wing is stationary relative to the oncoming flow, a propeller rotates. This creates a component of flow perpendicular to the axis of propeller rotation in addition to the flow along the axis of rotation resulting as the boat advances. Furthermore, the component of flow due to propeller rotation increases from zero at the center of the propeller hub to a maximum at the propeller tips. The geometric sum of the speeds of these two components of flow determines the net flow speed. The angle of flow to the propeller blades is a function of the relative speeds of the two components. Since the flow due to rotation increases along the propeller radius, the angle of the propeller chord must change along its radius to achieve proper flow angles to generate thrust.

So far, we’ve discussed the physics of propeller thrust without mentioning pitch and slip. We’ll get to these shortly after we explain the physics of some of the conditions experienced when propellers operate sub-optimally. Propellers tum when enough engine power is applied to overcome the water resistance to rotation. As the throttle is advanced, the propeller starts to turn and the boat starts to move forward. The combination of forward and rotational velocities determines the angle of attack at the propeller blades.

If we hammer the throttles before the boat picks up sufficient speed, the velocity due to propeller rotation can become much greater than that due to boat advance. Angle of attack increases. If the angle of attack becomes too large, a stall condition occurs. The rotational speed of the propeller begins to increase while the propeller loses thrust. This condition is often incorrectly called propeller slip. If you experience this, simply back off the throttle until a more favourable ratio of rotational and advance velocities is created to reduce angle of attack and eliminate the stall condition.

Another condition that occurs, that is also incorrectly called propeller slip, is due to ventilation. Here, air enters the propeller flow stream. This results in an air/water mixture that is less dense than water alone. The reduction in density causes a reduction in resistance to propeller rotation. As a result, propeller speed increases and thrust decreases. Ventilation generally occurs in a steep tum when part of the propeller gets closer to the surface or when a boat launches off a wave in rough seas. Outboards and stem drives have a horizontal plate above the propeller to reduce ventilation. Propeller design can accommodate ventilation and still provide effective thrust. An example is the surface piercing propeller.

The Propeller / Screw Analogy

The Propeller / Screw Analogy

Because of their complex geometry, the design and specification of propellers can be difficult. The propeller/screw analogy has been developed to simplify these processes. The fact that the distance travelled at a point along the radius increases with radius during a revolution, is a common trait of propellers and screws. Like a screw, propeller blade angles must vary from hub to tip so that all points on a blade advance the same distance each revolution. The distance travelled and the blade angles along the radius can be related geometrically. Thus a single parameter, the distance travelled during a rotation, defines blade angle as it changes with radius. This parameter is called pitch and generally specified in inches.

It is important to understand that pitch is not a precise parameter for defining a propeller. Propeller blades are rarely flat. Like airfoils, they have complex shapes to optimize thrust. Add to this the blade shape factors necessary to meet structural requirements, and you can see that blade angle becomes difficult to define and even more difficult to measure.

Measurements of pitch can vary with propeller manufacturers. I’ve purchased propellers for my boat where one manufacturer’s propeller was equivalent to another’s with two inches less pitch. Nevertheless, pitch is an important factor in both propeller design and selection.

So, What Is Slip?

If you assume that a propeller advances in water like a screw in wood, then you can calculate the speed of advance as a function of propeller rotational speed and pitch. The difference between this calculated speed of advance and actual measured boat speed is defined as slip.

Over the years, propeller designers have accumulated test data and calculated slip for a large variety of boats with different hull designs, power, weights, speeds and operating conditions. Categorizing similar boats produces a range of slip values for each group. Measurements of top speed for a given group with various power and weight ratios have resulted in empirical formulas to estimate top speed. A boat designer can then calculate top speed for his design using these empirical formulas. With the calculated top speed, the slip definition and an appropriate slip value, the designer can estimate a starting point for selecting propeller pitch. As far as I know, this is the only real use for slip factor.

The majority of physics books that I’ve seen that deal with propellers don’t even mention slip. I have seen slip discussed in propeller design books, but only for the purpose that I’ve mentioned above. I contend that since slip is based on a screw analogy that doesn’t describe the true physics of propeller operation, it too, as defined, is not a physical thing.

I have personally derived formulas to relate slip to physical things and the most interesting one that I’ve come up with is a geometric relationship between slip and angle of attack. This relationship shows that zero slip corresponds to zero angle of attack. Since zero angle of attack means zero thrust, you have to have slip to propel your boat.

Furthermore, since pitch is not universally defined for all propellers and drive trim results in an effective pitch different than that specified for a given propeller, slip comparisons can be flawed.

So why do propeller tests include slip factors? The only reason that I can think of is reader interest. It’s incorrect to equate slip with propeller efficiency and I’ve seen tests where the propeller with the least slip was not the fastest.

I’ve discussed the physics of propeller operation and the meaning and use of the term slip. I have also provided physical explanations for conditions where a propeller loses bite that are often incorrectly attributed to slip. I hope that I’ve convinced you that slip is not a physical thing and that you shouldn’t get too hung up on it when choosing a propeller for your boat.

If you’re still not convinced, I leave you with an example to ponder. I ask that you only think about this example and not try it, for safety reasons. Assume that you tie a line to your boat’s cleat and give it to a friend to hold. Start the boat and put the drive in gear. The propeller is now turning. Therefore, given pitch and rotational speed, you can calculate theoretical propeller/screw advance speed. If your friend is holding the boat stationary, its true speed is zero. Slip is then seen to be 100 percent. Tell that to your friend while he tries to hold back the boat.

Keyword : Boating, boating tips, propeller blades, propeller rotational speed and pitch, propeller slip, Propeller Theory 101, propellers Boating, boating tips, propeller blades, propeller rotational speed and pitch, propeller slip, Propeller Theory 101, propellers